Cognishift.Org Interview with Armenian Artist Fayenberg Sargsyan – The Cognishift Insider Magazine

FAYENBERG SARGSYAN

Born: 1948, Yerevan

1958 – Entered the artists’ studio of N. Kotanjyan and Sh. Vagharshakyan.

In the same year, he participated in an exhibition held in Czechoslovakia and was awarded First Prize and a Gold Medal.

1975 – Graduated from the Faculty of Drawing and Draftsmanship, Yerevan Pedagogical Institute.

1976–present – Lecturer at the same institute.

Since 1984 – Member of the Artists’ Union of Armenia.

Exhibitions

- 1967 – Moscow

- 1978 – Personal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Yerevan

- 1982 – Los Angeles

- 1998 – Holland

- 2002 – State Gallery of Armenia

His works are held in private collections in France, Germany, England, Lebanon, Yugoslavia, and the USA.

Interview by Mari Poghosyan & Dr.Prashant Madanmohan -Cognishift.ORg

1. What inspires you most to create?

When I paint, inspiration does not come from outside. I do not need anything special.

The moment I take the brush in my hand, I enter my own world and I can no longer come out of it.

The more I paint, the deeper I feel how much there is inside me that still has not been expressed.

While painting, I often feel as though I still do not know how to paint, because new ideas keep coming endlessly.

My paintings never repeat themselves. Each one has its own independent birth.

2. What was your first memorable work, and why?

When I was 16 years old, I painted a work on the theme “The Dancers.”

It participated in an all-Soviet-level competition held in Czechoslovakia.

That work received a Gold Medal.

The theme of the competition was “The World Through Children’s Eyes.”

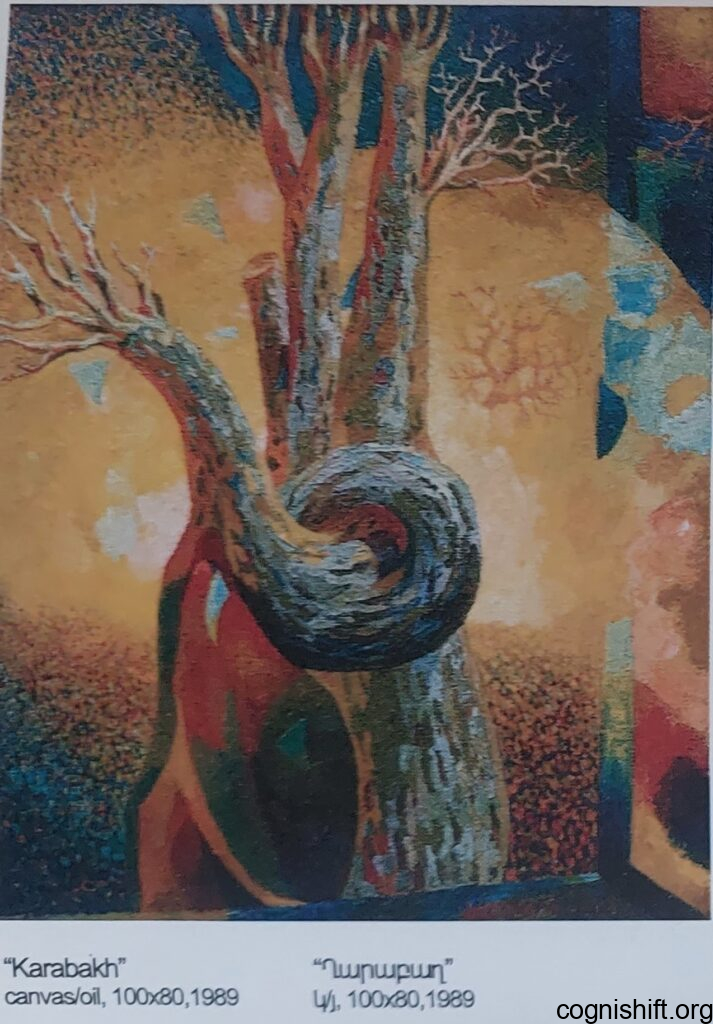

This Karabakh tree gives the impression as if it has been brought inside through the window.

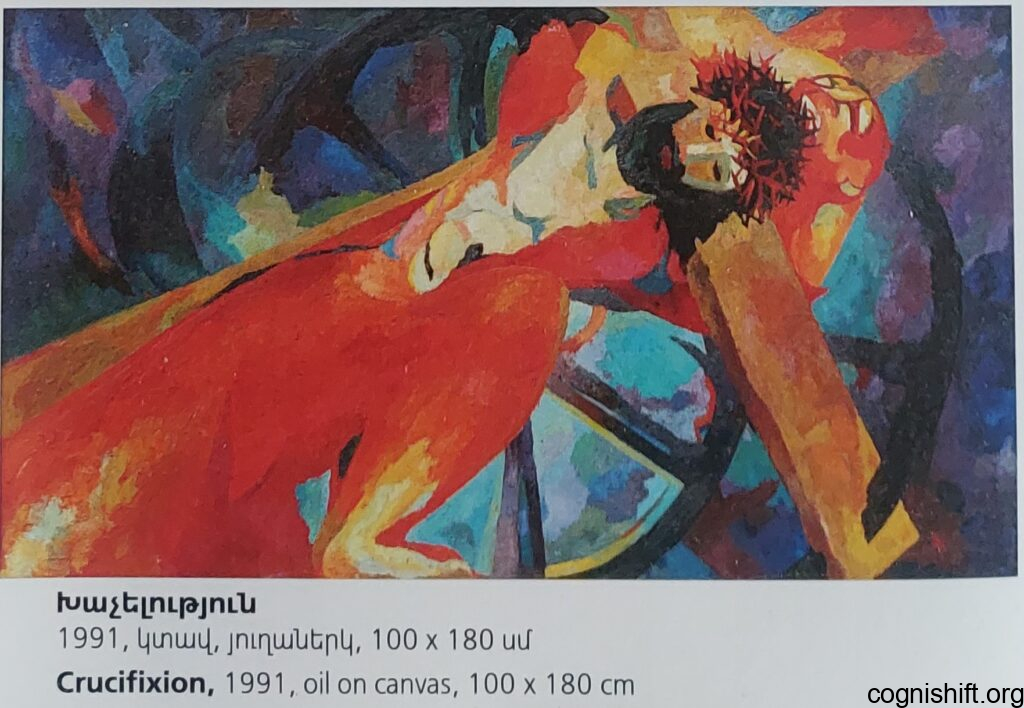

This is Christ. Every person carries their own cross.

And when one passes through the path of suffering, in the end—cleansed—one appears before God, the earth, or people, dressed in white. That is the true path of purification.

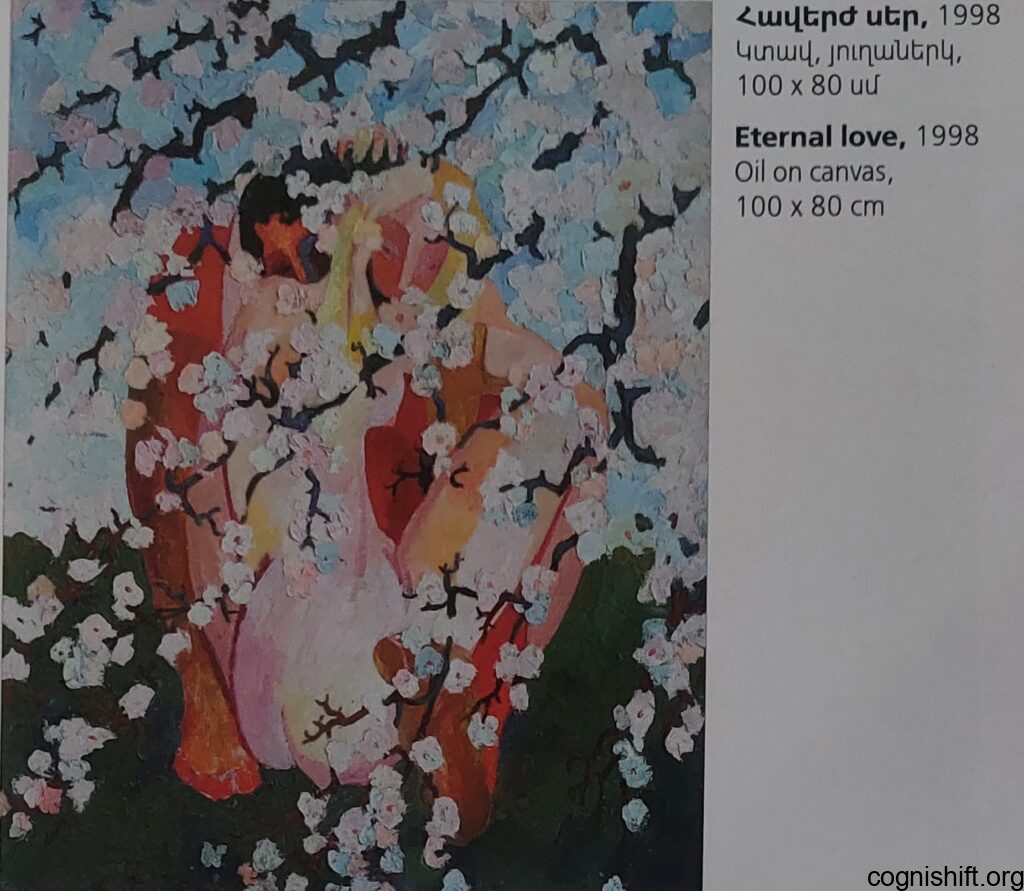

This is Love—Eternal Love. This painting is now in France.

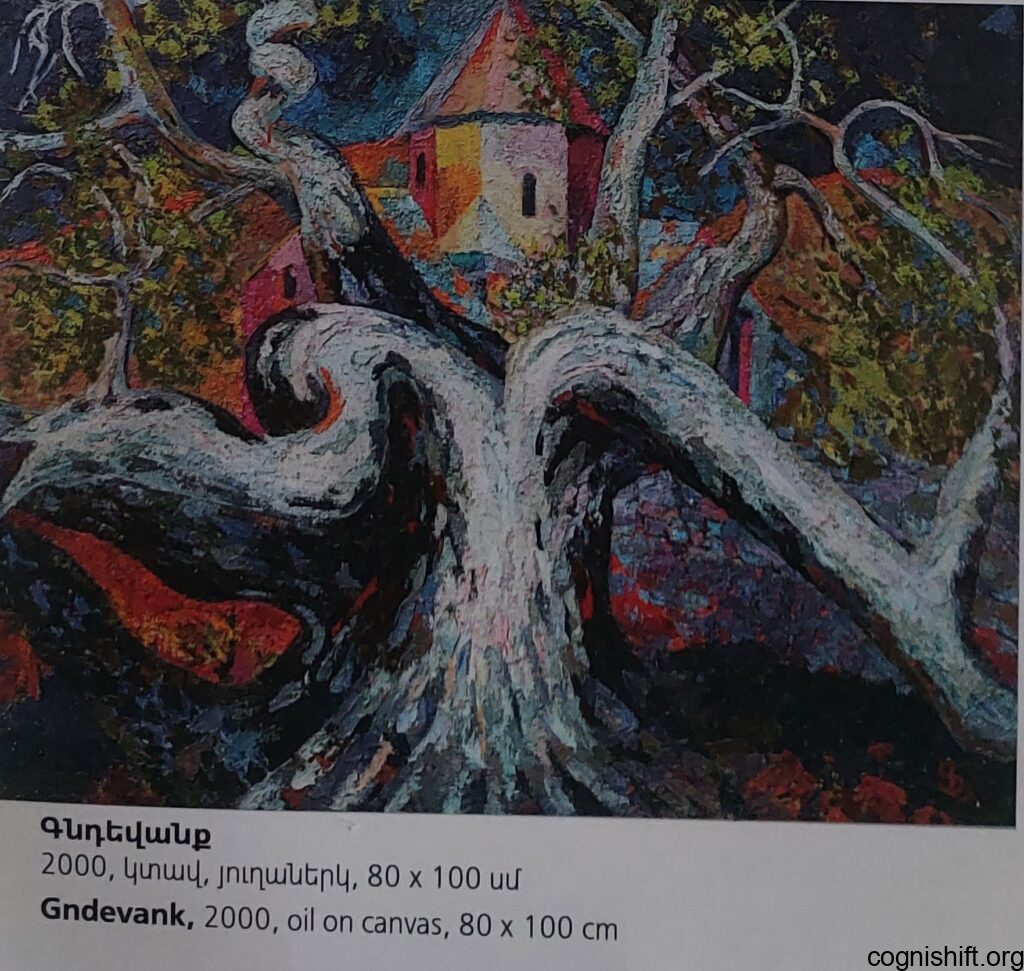

This painting is Gndevank, located in Jermuk.

There was a very interesting tree there, and I painted it in such a way that it creates the impression that the church was born from that tree.

The painting automatically raises a question: Was the tree there first, or the monastery?

Gndevank is a 12th-century monastery.

3. What themes recur constantly in your work?

The themes of my paintings are born spontaneously.

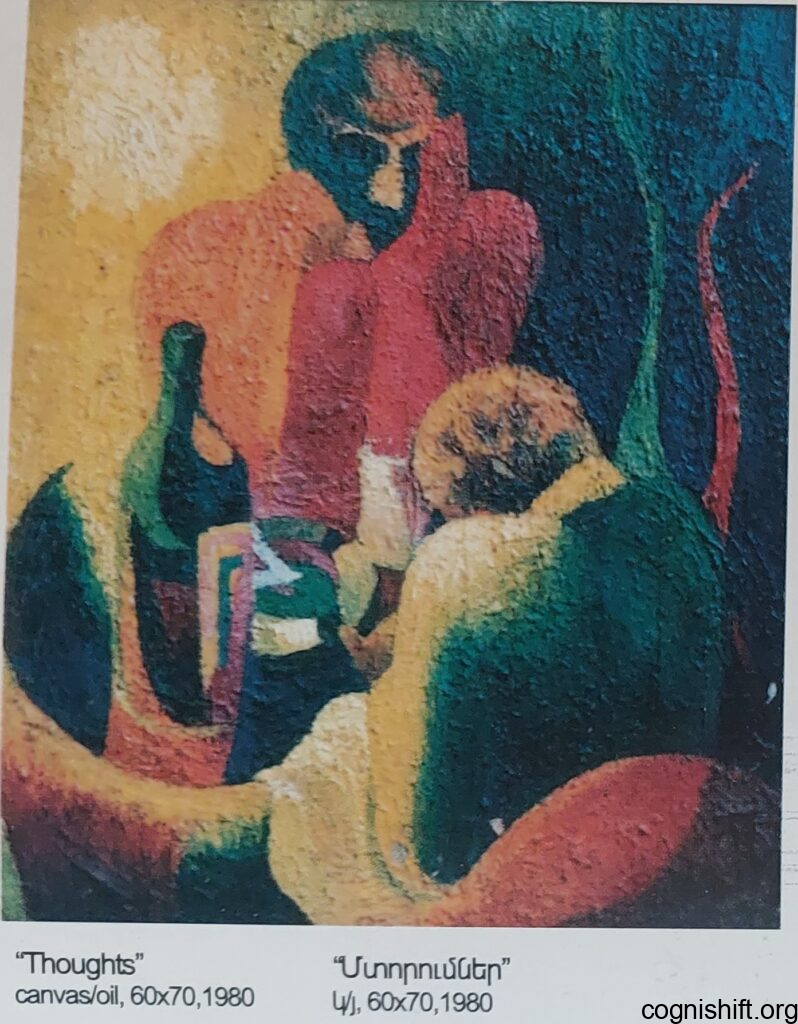

For example, this painting with my friend—I painted it when I was 18 years old.

We were sitting with friends, drinking, and from that moment this work was born.

The impression of the painting is such that it feels as if it was created by a very mature and experienced artist,

but at that time I was only 18.

4. How would you define your artistic style?

I create in different styles.

With realism, I try to create a living and precise image.

With abstraction, I convey my inner emotions and thoughts.

With cubism, I explore the multilayered and branched nature of reality.

Each style gives me the opportunity to discover new creative dimensions and to experiment with the language of art.

5. For you, is art a discovery or an unveiling of layers of memory?

Art, for me, is birth.

It is a continuous prayer that never ends.

When you paint, you do not only create an image—you see your inner prayer.

You see the sound of your own soul.

And through that image, through that prayer, you can be cleansed, freed from heaviness, and approach inner purification and balance of the soul.

This painting is The scream, which is now in France.

It tells the story of the moment Armenia became independent.

The painting is born from a scream—from thorns that simultaneously pierce the skin and the soul, forcing one to cry out.

This scream does not depict itself; it exists in the intersection of strength, pain, and freedom, leaving the viewer to feel and contemplate.

Light—because after it, nothing exists.

A person is in the world exactly as they speak.

When you paint, it transmits energy to people.

Our creation is complex in its form, like the universe.

Music can be immediately understood and felt by people, but painting is much deeper—with its cosmic lines, rhythms, and forms, as if it is connected to the universe, as if the painter himself is a small universe.

Later, it becomes clear that the painting “speaks” in its own way—it creates an interesting sensation, it is entirely soul.

Not even the artist or his friends always understand what he feels.

At that moment, a person alone must know when to stop and remain silent.

**6. What do you wish to convey to future generations through your art?

Is there a question you are trying to answer through it?**

There are questions whose answers are never complete.

No matter how much you answer, something always remains unsaid.

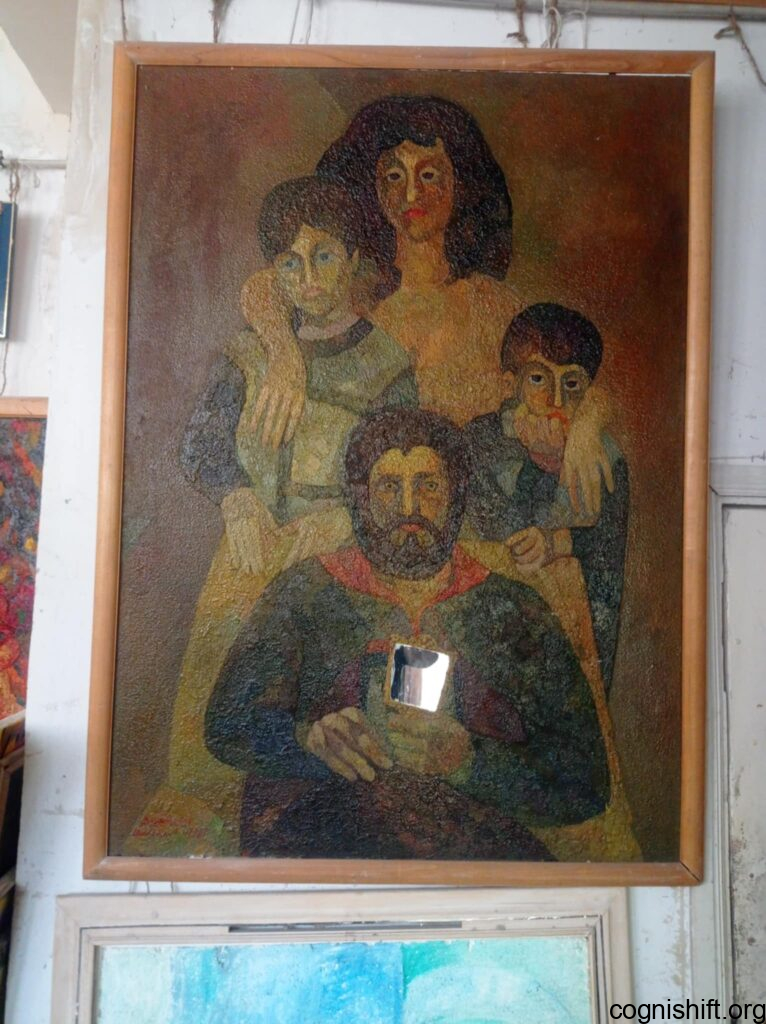

For example, in my family painting.

There is a real mirror in the canvas. It is my family portrait, and I hold it in my hand.

The person who approaches the painting becomes part of that painting, and the painting “works”—it begins to speak, to feel, and to interact.

Then the question arises: Does that person have the right to enter that family, that state, or that circle of friendship?

At one time, we even wanted to gift this painting to Gorbachev, so that he would look at himself and try to understand whether he had the right to enter that family’s world.

The painting contains stories—Karabakh events, memories, and emotions—that are constantly touched by the viewer.

At an exhibition organized at our university, Garegin I visited.

He approached me and said:

“You know, I have traveled the whole world, but I have never seen such a painting.”

Now the little boy in that painting is no longer alive.

After the Surmalu events, my son died.

I dedicated this painting to my son, portraying his soul as it flies, touching the canvas with its wings.

This painting has become the memory of my son and the cry of souls that continue to live within paintings.

This painting is abstract to portray the mixed and restless state when my soul is in turmoil.

My son participated in the war—he was a participant of the Karabakh war.

He returned and later died in a naïve, defenseless manner.

He fell into a pit. Beside him were his wife and child.

He gave the child to the woman and said,

“Run from here. My leg is broken, I cannot.”

The woman and child survived; he died.

The painting conveys the pain of that tragedy, human loss, and the heavy sensation of the soul.

Through imaginary figures, it becomes the cry inside me.

This painting participated in exhibitions in various countries, and through it I met Minas Avetisyan.

When he saw the painting, he asked, “Who painted this?” and asked my teachers to introduce him to me.

7. Is creating art a rebellion against oblivion?

You know, among Armenians there is always rebirth.

Look at Saryan, Kojoyan—there are magnificent works that show the spiritual strength our nation has had.

No one has been able to kill it. It has been kept alive and passed on to us.

Just like your phoenix bird—that is how it is. ( refers to Mari Poghosyan’s Original painting – Phoenix 2025-(Lalit Kala Akademi – The God Of Deserted Memories Art Exhibition )

Yes, that is our entire strength, our power, which we often do not understand and do not even realize.

Now I am painting Komitas, and I think about how to portray him so that he truly becomes a “priest” within himself.

After much thought, I chose the apricot tree.

Komitas is kneeling in black garments, and the branches of the tree are flooded with blossoms.

The painting leaves the impression that Komitas himself is that tree—powerful, filled with priestly strength, a figure of an entirely different dimension and significance.

8. In your opinion, how have Armenian artists preserved culture after the genocide?

There has always been rebirth among Armenians.

Look at Saryan, Kojoyan—those works show the spiritual force our nation possessed.

No one could destroy it. It lived on and was passed to us.

That is our strength—like the phoenix.

Yes, this is our power, which we often do not recognize or realize.

9. Is creating art a rebellion against forgetting?

Let us take music.

I have listened a lot to ancient Indian music—its rhythm and form lead toward the cosmos, lifting the soul.

I feel the same power in Komitas’ music.

It is genius and divine creation.

It gives something unique to a person—as if God Himself grants that gift.

10. Can art preserve what history has forgotten?

Histories often play games within themselves.

Take the most powerful country—over time it collapses, another rises, reaches its peak, becomes powerful, and then no traces remain.

It is incomprehensible, but Armenia exists and will always exist.

It has never exceeded its measure. It has always been noble, never cruel.

Some force—as if unseen—has preserved Armenia.

Art is the language of a nation.

It preserves our spirit, our history, and our inexhaustible strength.

11. Can art unite peoples and bring peace between cultures? How?

Art always brings peace.

Many simply do not understand it.

Painting is a universal language.

When you see a painter’s work, you speak, feel, and communicate in that language.

**12. French art sought freedom, Armenian art survival, Indian art spirituality.

What does our time seek—memory?**

All art seeks the soul.

Even the most extreme abstraction eventually purifies itself, opens, and reveals inner spiritual and cosmic light.

Painting is not merely skill.

It is a divinely given ability—a language through which a person speaks with the world and with a calm soul.

13. Is art the memory of the future or a witness of the present?

Art is the birth of happiness.

It is neither old nor new—it is divine.

14. Dr. Leander’s Closing Question

“Art may not be created for the present.

It is the memory of the future.

Mr. Fayenberg, if tomorrow’s world were to remember only one feeling from your art, what should it be?”

That feeling comes from one thing—that people be happy.

I have one painting that many people talk about.

People who stand beneath it later have children.

I created that work with that very desire—to have a child.

The painting formed rhythmically and symbolically, so that at first glance one does not even understand what is depicted—then suddenly another reality opens inside.

There have been many such cases, and even I do not understand how that painting affects people.

But every time I hear that they have had a child, I feel sincere happiness, because their wish has been fulfilled.

That has always been my greatest desire—that people be happy.

— Translated faithfully for The Cognishift Insider Magazine

by Mari Poghosyan